Sustainability

Waste to Energy Project

Pua-ngoen Sumalee, a cook for Ban Thap Hai School, is busy preparing food for members of a biogas production and garbage recycling training and workshop. Her cooking, preparing a large pot of rice and two dishes, would have been but another ordinary event had it been prepared with heat from a gas cylinder that can be found in most kitchens.

Instead, Pua-ngoen is cooking with biogas produced in a digestion tank located on the floor next to the kitchen.

The cooks at Ban Thap Hai School have not used commercially available cooking gas for years, ever since they joined the village's biogas project. The same is true of many other families in Nong Saeng district, Udon Thani Province.

Adopting biogas has many benefits. It provides savings on household expenses while being an effective way to dispose of garbage.

Not too far from the kitchen, Ban Thap Hai School director Chatchai Laokliengdee is demonstrating how to add "raw materials" into a biogas digestion tank. He pours leftover food and chopped Napier grass into the tank by using a long stick to push the material down.

The fermentation tank looks like a large capsule. It is covered with a black plastic sheet, swollen by the pressure of the gas inside. Some people said the gas lagoon appears like a balloon that can't float.

"I built the first pond three years ago," Chatchai says as he pours more raw material into the tank. "As it turned out, one lagoon did not produce enough gas. The school has to feed 60-70 children, 20 days a month," the school director says.

Ban Thap Hai is a school for children from kindergarten to primary school. Even though it does not cater to a large number of students, it has to provide lunch for every single student. In the past, the school had to buy one 15-kilogram gas cylinder per month.

The school director decided to join PTTEP's biogas production project, which provided him with the equipment and funding needed to generate the alternative fuel. Once he saw that the use of biogas helped him save significantly on cooking gas, he requested subsidies to build the second lagoon.

Ban Thap Hai School has been run on the "philosophy of sufficiency economy" as championed by His Majesty King Bhumibol Adulyadej for many years. It has sheds where chicken and frogs are kept, some for sale while others are to be released back into nature. The school also rears earthworms whose feces are used as fertilizer.

The biogas production project fits in perfectly with the school's teachings and philosophy. During the past few years, the school had almost no need for commercial cooking gas and has bought only two gas cylinders.

This is compared to its reliance on one gas cylinder per month before the biogas came along. In three years, the school has saved over 14,000 baht.

When it comes to feeding the biogas ponds, janitors and students are tasked with the job according to a predetermined schedule. During school holidays, however, there is no leftover food while the lagoon should not be left without fermentation process. The school, therefore, decided to acquire a piece of land to plant Napier grass commonly used to feed cattle.

The chopped grass can be used to fill in the biogas lagoon. Sometimes, the school also trades the grass for cattle dung, which can also be used as materials to produce biogas.

"We can probably ask for the cattle dung for free, but farmers can keep it to use as fertilizer. They can sell it as well at about 35 baht per sack," the school director says.

Chatchai adds that cattle herders sometimes go to the school's patch to harvest grass for their livestock. Some even bring their animals to the school and let the cattle roam there so that they don't have to keep a watch on them.

The director said trading grass for cattle waste is a win-win approach for the school and cattle farmers. The school receives material for its biogas production while the farmers do not need to spend their time finding grass to feed their cattle.

In the future, the school may raise cattle itself so that it can use their dung for its biogas production.

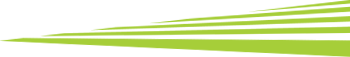

A biogas lagoon looks like a large balloon. The plastic cover appears tight and swollen from the biogas accumulated inside.

The lagoon is about 1.7 meters wide and four meters long. It is about 80 centimeters deep on the front end widening to about 1 meter deep at the other end.

After digging up the lagoon, villagers then line it with a large plastic sheet

Rundorn Pimda, who serves as a community coordinator, recounts how to prepare a biogas lagoon from his own experience.

"We will connect PVC pipes to the mouth of the tarpaulin and its rear end. The connections will be wrapped and the one at the mouth serves as a material feeder while the one at the bottom will drain excess water. After that, we use an air pump to inflate the tarpaulin sack into shape then add water into it," Rundorn says.

The water must be added until its level is higher than the PVC pipe. This will prevent the air and gas from leaking. Once the biogas lagoon is inflated, animal waste can be put into it. Animal waste is preferred as a seed material as it produces more gas. Once there is enough methane in the lagoon, leftover food or more animal waste can be added to it.

The production of biogas inside the lagoon is a rather simple process. As the animal waste, garbage or organic leftovers decompose, the digestion process naturally produces gas.

In case too much raw material is added into the pond, or it rains, excess water will be drained off the rear end of the lagoon. Fermented water can be used to water trees.

The lagoon will also be equipped with another valve pipe where gas will be allowed to travel. This pipe is then connected to various kitchens in different households.

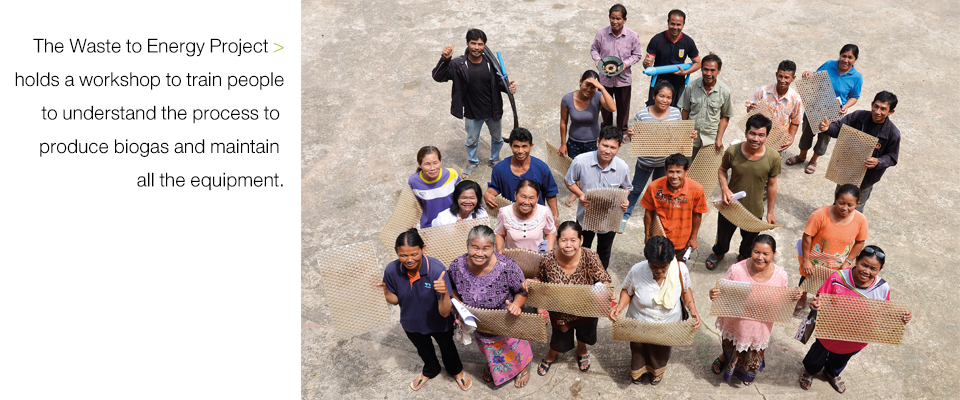

Biogas production and garbage recycling training were conceived after people in Ban Thasee decided to get rid of the animal waste, especially those from cattle that were scattered around their village. The project commenced in 2010 with 42 ponds. Two years later in 2012, the villagers formed a group and asked for a grant from PTTEP which operates the Sinphuhom natural gas exploration and production nearby. The villagers did so after they learned from word of mouth that biogas ponds can produce gas for household use.

Daeng Uantem, a member of Ban Thap Hai in Saeng Sawang Sub-district in Nong Saeng District who joined the project 3 years ago, says it is not a difficult thing to do. "It helps us save a lot. It's not difficult either. Just dig a pond. After that, PTTEP staff installed the gas bag and laid the pipeline for us. We can put any household waste into the pond, water, or leftover food. I used to buy up to six gas cylinders a year before. Now, I only need to buy one," Daeng says.

Daeng's success has drawn others into the biogas project.

Not too far from the school lies a small plot of land, complete with a water pond and a cowshed, which belongs to Ai Bootprom, the latest member of the biogas project. A one-meter-deep pond has been prepared. Once everyone is ready, a biogas bag will be installed.

"I think it's good to use and it's economical," says Ai after seeing how her neighbors have relied on the alternative fuel for a few years.

The five cows in the shed give Mae Ai hope that they will produce enough dung to feed into the lagoon and turn it into fuel. She will compliment it with biodegradable food residue as her neighbors told her.

Mae Ai has mastered the theory. All she needs to do now is to start practicing it.

Before long, it will transport gas to Mae Ai's kitchen. Yet another family will be able to produce cooking gas by themselves using animal waste and leftovers.

As another biogas lagoon is coming into action, it will serve as a model for others to follow.

In 2012, PTTEP first implemented this project in Sang Sawang Sub-district, Nong Sang District by installing 36 Biogas kits at Ta Si Village and 6 kits at Tab Hai Village. Later, the project has been replicated to cover villagers in Tab King Sub-district. Up to date, there are 700 Bio-gas pits in the area.

To date, more than 700 households in Thailand and abroad have signed up for PTTEP's Waste to Energy Project, having cut their expenses on cooking gas by over 4,200 THB per household per year or a total of 2,700,000 THB per year. The project has disposed over 325 tonnes of biological waste and at least 470 tonnes of household waste per year. At least 75 tonnes of organic fertilizers have been produced, saving expenses of fertilizers for their plantation.

PTTEP has carried out analysis on Social Return on Investment (SROI) of this project by measuring the social impact of the program with the financial quantification calculation (monetization).

This method is intended to measure the value of the financial impact of the program that compares to the value of the impact to the cost of the program that has been invested into.

It appears that the value of the SROI ratio is 3.66 : 1.

...the sea has become our home and so we are conscious of our responsibilities...

...the sea has become our home and so we are conscious of our responsibilities...

PTTEP is E&P company in Thailand, exploring for sustainable sources of petroleum for the countries we operate

PTTEP is E&P company in Thailand, exploring for sustainable sources of petroleum for the countries we operate

SIGN IN

SIGN IN SEARCH

SEARCH